Facilitating reproducibility in academic publications

Overview

Teaching: 90 min

Exercises: 60-90 minQuestions

How does academic publishing work?

What is the IMRAD format?

What are reporting guidelines and why are they useful for reproducibility?

How can we judge the quality and credibility of a preprint

Objectives

Understand how the academic publishing process works

Know about IMRAD sections and detect content in articles efficiently

Find appropriate reporting guidelines and know their advantages

Review a preprint using a simple checklist

1. Primer on academic publishing

Why publish?

Results of research are published in the literature such that

- findings get disseminated

- other researchers can assess “what is known”

- findings can get synthesized into overall evidence

- evidence can inform policy

but also such that

- researchers can document their output

- researchers can be assessed for career advancement

- researchers can build a “reputation”

⇒ Publication advances science and the career of scientists

Where to publish?

Most scientific publications are in academic journals or books. Journals may be

- discipline specific or across several disciplines

- run by learned societies or by commercial publishers

- open or closed access

- have more or less “impact”

- existing for over 100 years or only a short time

- exist in print/online or only online

- “predatory”

There may be more than 30’000 journals publishing 2’000’000 articles, aka papers, per year.

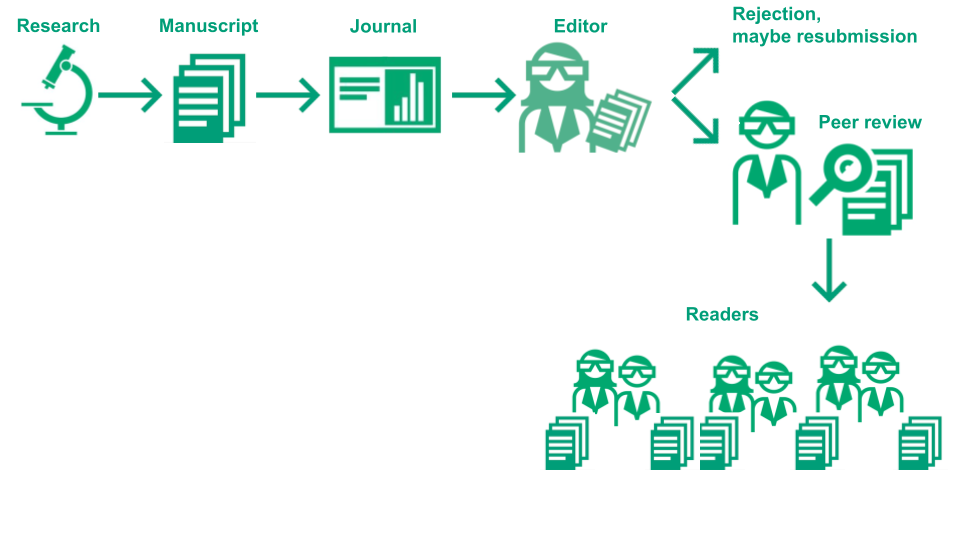

How does the process of publication in journals work?

Authors have to follow several steps, which are in general:

- Carry out a study or another type of research project, write an article, select a journal

- Submit the article to peer review at the journal

- The article will be assigned an editor and undergoes formal checks

- The editor decides if it will be peer-reviewed or rejected directly (desk-rejection)

- The editor searches peer reviewers, usually at least two independent and anonymous experts

- The article is peer-reviewed resulting in review reports

- The editor assesses the reports and makes a decision among:

- Rejection: the article cannot be published at this journal

- Revision: the article has to undergo changes, sometimes major, before publication

- Acceptance: the article can be published as it is, most often conditional on small cosmetic changes

The below image illustrates this process:

Image Credit: (Part of) Illustration of the academic publication process by the Center for Reproducible Science (E. Furrer), CC-BY, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7994313.

What is a doi and what is Crossref?

Since the goal of scientific articles is to contribute to the advancement of science they need to be findable and identifiable for future work. For that a necessary condition is that they have a unique identifier, which is nowadays, of course, a digital identifier.

From Wikipedia:

“A digital object identifier (DOI) is a persistent identifier or handle used to identify objects uniquely, standardized by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). An implementation of the Handle System, DOIs are in wide use mainly to identify academic, professional, and government information, such as journal articles, research reports, data sets, and official publications. DOIs have also been used, however, to identify other types of information resources, such as commercial videos.”

Since a DOI is a unique identifier you can find any article by concatenating https://doi.org/ and the DOI of the article and pasting it in the URL field of your browser. Try it out with 10.1186/s13059-015-0850-7. DOIs are issued by, for example, Crossref:

“Crossref (formerly styled CrossRef) is an official digital object identifier (DOI) Registration Agency of the International DOI Foundation. It is run by the Publishers International Linking Association Inc. (PILA) and was launched in early 2000 as a cooperative effort among publishers to enable persistent cross-publisher citation linking in online academic journals.”

Hence Crossref is the organisation which registers most doi for academic publications. (Source Wikipedia)

Indexing of journals/publications

Indexation of a journal, i.e. the inclusion of its articles in a meta data base, is considered a reflection of the quality of the journal. Indexed journals may be of higher scientific quality as compared to non-indexed journals. Examples of indexes are:

- Pubmed/MEDLINE https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

- Directory of Open Access Journals https://doaj.org/

- Thomson Reuters Journal Citation Reports https://clarivate.com/webofsciencegroup/solutions/journal-citation-reports

Many universities also have in-house databases for the articles produced by their researchers: at the University of Zurich, for example, this is ZORA https://www.zora.uzh.ch/

Why is peer review part of the publication process?

- Peer review allows to check and improve research.

- Peer review serves as scientific quality control.

- Peer review provides a form of self regulation for science.

- Peer review makes publication (more) trustworthy

Before you review for the first time see Open Reviewer Toolkit

Known issues of the process

Issues with peer review

- Anonymity of peer reviewers but not authors

- Conflict of interest of peer reviewers: plagiarism, delays, favouritism, biases

- Peer reviewers may not be competent enough

- Peer reviewers are volunteers and almost not rewarded

- The process is slow and unpredictable

- Increasing numbers of publications make it more and more unfeasible

Issues with the publication system

- Sensational results are privileged over solid but less sensational research

- Lacking equity, e.g. already published authors are given cumulatively more credit (Matthew effect)

- Expensive either in subscription fees in order to be able read a journal or processing charges to publish open to everyone

- Evaluation of researchers is publication based and this incentivises fast but not rigorous research (“publish or perish”)

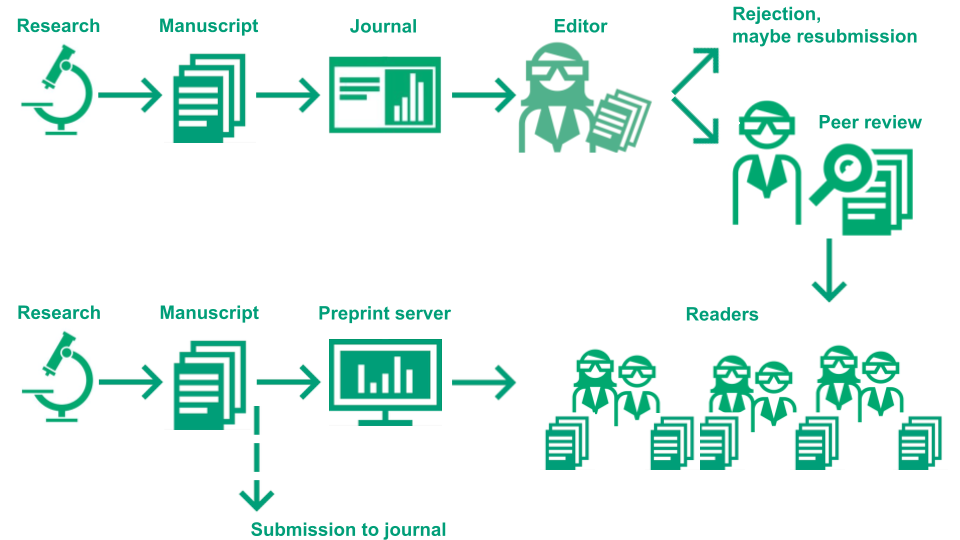

Preprints

Preprints are a relatively new form of publication which helps to overcome some of the issues with peer review and with the publication system. See the extension of the above graphic including preprints in the publication process:

Image Credit: Illustration of the academic publication process by Eva Furrer, CC-BY, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7994313.

Image Credit: Illustration of the academic publication process by Eva Furrer, CC-BY, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7994313.

See also J Berg et al. for a comment on the introduction of preprints in Biology: https://www.science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/science.aaf9133.

Quiz on academic publishing

Peer review

Which statements are correct for the practice of peer review in academic publishing?

- peer review contributes to keep the quality of publications to high standard

- peer reviewers are financially rewarded for their contribution

- peer review may take a long time and its outcome does not always depend on the quality of a publication

- peer reviewers are always objective experts not pursuing their personal interest

- one publication is always peer reviewed by exactly one expert

Solution

T peer review contributes to keep the quality of publications to high standard

F peer reviewers are financially rewarded for their contribution

T peer review may take a long time and its outcome does not always depend on the quality of a publication

F peer reviewers are always objective experts not pursuing their personal interest

F one publication is always peer reviewed by exactly one expert

Unfairness

The publication system is unfair since authors from prestigious institutions or authors with already a lot of publication are privileged, for them it is easier to publish since editors and reviewers decide in their favor more often. Such a type of effect is not unique to academic publishing but occurs in different aspects of society.

A common name for this effect is:

Solution

Matthew effect

Preprints

Why do preprints help to overcome some of the issues with peer review and with the publication system?

Solution

Preprints avoid conflicts of interests of peer reviewers, allow certain and fast publication and are completely free of charge.

2. What is the IMRAD format?

What is IMRAD?

The acronym IMRAD stands for “Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion”. IMRAD is a widespread format in the biomedical, natural and social science research literature for reports on empirical studies. It is a convenience to readers because they can easily find the specific information they may be looking for in an article. See the article of J Wu https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10980-011-9674-3 for a quick overview illustration:

Image credit: Illustration of the IMRAD concept, by Eva Furrer, CC-BY, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7994280.

Image credit: Illustration of the IMRAD concept, by Eva Furrer, CC-BY, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7994280.

R Day writes about the history of scientific publication in his article, “The Origins of the Scientific Paper: The IMRAD Format”. He specifically mentions the scientific method and its cornerstone the principle of reproducibility of results. The IMRAD Format has been introduced in order to represent the steps of the scientific method.

“Eventually, in 1972, the IMRAD format became “standard” with the publication of the American National Standard for the preparation of scientific papers for written or oral presentation.”

R Day American Medical Writers Association, 1989, Vol 4, No 2., 16–18. This article is not easily obtainable online, potentially your library can obtain it for you. If this is not possible, please contact the authors of this lesson.

What is the scientific method?

The Center for Reproducible Science at the University of Zurich uses a simplified graphical representation of the scientific method in its communications:

Image credit: Illustrations of meta research and the research cycle by Luca Eusebio and Eva Furrer, CC-BY, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7994222.

Image credit: Illustrations of meta research and the research cycle by Luca Eusebio and Eva Furrer, CC-BY, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7994222.

“What is the Scientific Method?” is a philosophical question that we can not answer in full detail here and it may be one of the questions to which there is no single correct answer. We will use the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy definition as a first approximation:

“Often, ‘the scientific method’ is presented in textbooks and educational web pages as a fixed four or five step procedure starting from observations and description of a phenomenon and progressing over formulation of a hypothesis which explains the phenomenon, designing and conducting experiments to test the hypothesis, analyzing the results, and ending with drawing a conclusion.”

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/scientific-method/

This view coincides with a common approach to empirical research, even if it may be an oversimplification and a strong generalization, we assume an underlying scientific process for this lesson that is close to such an approach.

What should the IMRAD sections contain?

In 1997 the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors published “Uniform Requirements” on the structure of articles:

“The text of observational and experimental articles is usually (but not necessarily) divided into sections with the headings Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion. Long articles may need subheadings within some sections (especially the Results and Discussion sections) to clarify their content. Other types of articles, such as case reports, reviews, and editorials, are likely to need other formats. Authors should consult individual journals for further guidance.”

The Uniform Requirements have been updated in December 2021 and the most current version can be found here: http://www.icmje.org/about-icmje/faqs/icmje-recommendations/ The 1997 version of the requirements is avaliable here: https://www.icmje.org/recommendations/archives/1997_urm.pdf.

The document contains much more than advice on structuring a manuscript, e.g. authorship roles, peer review roles etc. Please read the chapter/section “Manuscript Sections” in one of the two versions in order to get an overview of the expected content of the IMRAD sections.

There is a long list of journals that state that they follow these requirements http://www.icmje.org/journals-following-the-icmje-recommendations/

Quiz on IMRAD

Cornerstone of the scientific method

Hippocrates is credited as the discoverer of the scientific method. But he did not clearly state its cornerstone. The cornerstone of the scientific method is the:

Solution

reproducibility of results

Introduction section

The introduction section in an article following the IMRAD structure should contain?

- a short overview over the data and main conclusions of the article

- the purpose/objective of the presented research

- a complete and detailed background of the wider research area

Solution

F a short overview over the data and main conclusions of the article

T the purpose/objective of the presented research

F a complete and detailed background of the wider research area

Methods section

The methods section in an article following the IMRAD structure should contain

- a descriptive analysis of the collected data such that appropriate methods can be chosen for the analysis

- enough information such that a reader would in theory be able to reproduce the results

- only information that was available before data collection

Solution

F a descriptive analysis of the collected data such that appropriate methods can be chosen for the analysis

T enough information such that a reader would in theory be able to reproduce the results

T only information that was available before data collection

Statistical methods

The statistical methods subsection of the methods section in an article following the IMRAD structure should contain

- detailed information software and packages

- only contain p-values an no effect sizes or estimates of the precision

- distinguish pre-specified parts of the analysis from parts that have been done in an explorative way after looking at the collected data

Solution

T detailed information software and packages

F only contain p-values an no effect sizes or estimates of the precision

T distinguish pre-specified parts of the analysis from parts that have been done in an explorative way after looking at the collected data

Discussion section

The discussion section in an article following the IMRAD structure should contain

- limitations of the study

- those conclusions in view of the goals of the study that are supported by the results

- a detailed summary of all results

Solution

T limitations of the study

T those conclusions in view of the goals of the study that are supported by the results

F a detailed summary of all results

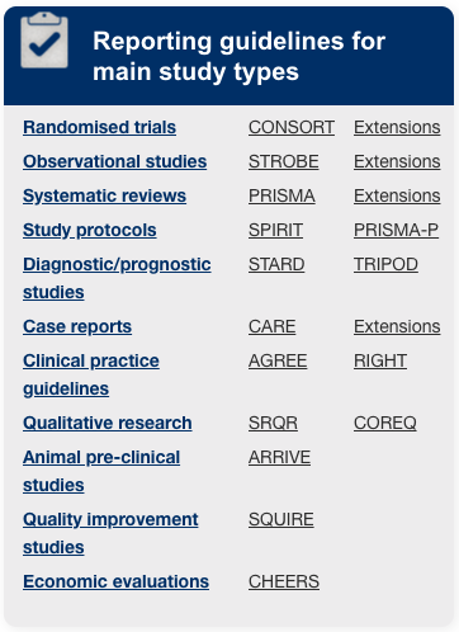

3. Reporting guidelines

Reporting guidelines are checklists that are based on wide agreement in a field providing more detailed guidance on the contents of IMRAD section.

Goals of reporting guidelines

The goals of Reporting Guidelines are summarized in I Simera and D Altman https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ijcp.12168. They summarize some key principles for responsible reserach reporting:

“Researchers should present their results clearly, honestly, and without fabrication, falsification or inappropriate data manipulation.”

“Researchers should strive to describe their methods clearly and unambiguously so that their findings can be confirmed by others.”

“Researchers should follow applicable reporting guidelines. Publications should provide sufficient detail to permit experiments to be repeated by other researchers.”

Good reporting is an ethical imperative

The WMA Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects states:

“Researchers, authors, sponsors, editors and publishers all have ethical obligations with regard to the publication and dissemination of the results of research. Researchers have a duty to make publicly available the results of their research on human subjects and are accountable for the completeness and accuracy of their reports. All parties should adhere to accepted guidelines for ethical reporting. Negative and inconclusive as well as positive results must be published or otherwise made publicly available. […]”

Good reporting is required by many journals

For example the Reporting requirements of the Nature Research journals aim to improve the transparency of reporting and reproducibility of published results across all areas of science. Before peer review, the corresponding author must complete an editorial policy checklist to ensure compliance with Nature Research editorial policies; where relevant, manuscripts sent for review must include completed reporting summary documents.

Nature portfolio Reporting Summary https://www.nature.com/documents/nr-reporting-summary-flat.pdf Nature Reporting requirements and reproducibility editorials https://www.nature.com/nature-portfolio/editorial-policies/reporting-standards#editorials

Database of reporting guidelines

“The EQUATOR (Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research) Network is an international initiative that seeks to improve the reliability and value of published health research literature by promoting transparent and accurate reporting and wider use of robust reporting guidelines.”

“It is the first coordinated attempt to tackle the problems of inadequate reporting systematically and on a global scale; it advances the work done by individual groups over the last 15 years.”

http://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/

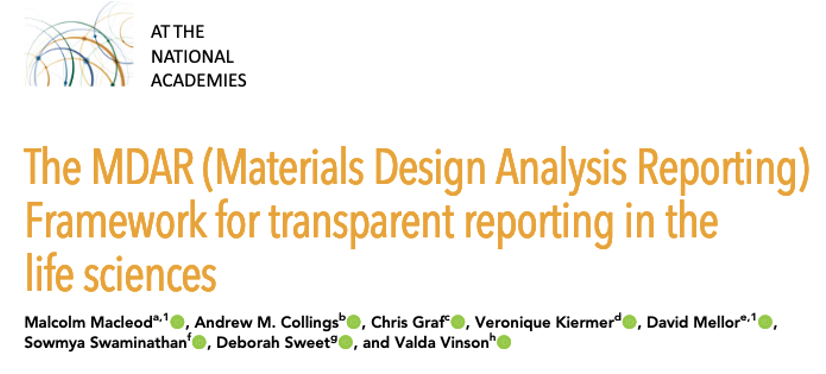

The MDAR framework

“We were motivated to develop the MDAR Framework as part of our own and others’ attempts to improve reporting to drive research improvement and ultimately greater trust in science. Existing tools, such as the ARRIVE guidelines, guidance from FAIRSharing, and the EQUATOR Network, speak to important sub-elements of biomedical research. This new MDAR Framework aims to be more general and less deep, and therefore complements these important specialist guidelines.”

M McLeod et al. https://www.pnas.org/content/118/17/e2103238118

Other examples of reporting guidelines

M Michel et al. http://dmd.aspetjournals.org/content/dmd/48/1/64.full.pdf

T Hartung et al.https://www.altex.org/index.php/altex/article/view/1229

S Cruz Rivera et al. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-020-1037-7.pdf

M Appelbaum https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2018-00750-002.html

⇒ also available for qualitative and mixed methods

R Poldrack et al. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1053811907011020?via%3Dihub

L Riek https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.5898/JHRI.1.1.Riek

Benefits of reporting guidelines

Benefits for researchers

Guidelines helps at protocol stage, e.g. with examples how to reduce the risk of bias

Useful reminder of all necessary details at writing stage, especially for junior researchers

Appropriate reporting allows the replication or inclusion in meta research projects

Adherence increases chances of article acceptance at journals

Benefits for peer reviewers

Peer review is an important step but limited guidance is available

Key issues and methods that should be covered in an article can be found in reporting guideline

If journal requests a completed checklist approach even easier

Criticism can be justified by pointing to reporting guideline (or their explanation documents)

But not a guarantee for a high quality study

Example: reporting of methods

“t-tests were used for comparisons of continuous variables and Fisher’s Exact test or Chi-squared test (where appropriate) were used for comparisons of binary variables”

versus

“The primary outcome, time to […], was analysed using a two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The secondary outcomes of […] were analysed using the Chi square and Fisher’s exact test, respectively, and the secondary outcome of time to […] was analysed using a two- sample Wilcoxon rank-sum test. All analyses were carried out on a per protocol basis using [software version]”

courtesy of M. Schussel of the Equator Network

Quiz on reporting guidelines

Reporting guidelines

Reporting guidelines are

- only used in biomedicine

- based on a wide consensus of experts

- mainly useful for the reader

Solution

F only used in biomedicine

T based on a wide consensus of experts

F mainly useful for the reader

JARS quiz 1

Look at the Journal Article Reporting Standards for Quantitative Research in Psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board Task Force Report (JARS)

M Appelbaum et al. https://doi.apa.org/fulltext/2018-00750-002.htmlThe guideline suggests to to group all hypotheses, analyses, and conclusions into

- significant and non-significant

- primary, secondary, and exploratory

- novel, derived, and replication

Solution

F significant and non-significant

T primary, secondary, and exploratory

F novel, derived, and replication

JARS quiz 2

Look at the Journal Article Reporting Standards for Quantitative Research in Psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board Task Force Report (JARS)

M Appelbaum et al. https://doi.apa.org/fulltext/2018-00750-002.htmlFor publications that report on new data collections regardless of research design the guideline includes information on:

- where to report on registration of the underlying study

- where to report on the availabililty of data

- where to report a manual of procedures allowing replication

Solution

T where to report on registration of the underlying study: mainly for clinical trials

T where to report on the availabililty of data: specifically only for meta analysis

T where to report a manual of procedures allowing replication: specifically for experimental studies

JARS quiz 3

Look at the Journal Article Reporting Standards for Quantitative Research in Psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board Task Force Report (JARS)

M Appelbaum et al. https://doi.apa.org/fulltext/2018-00750-002.htmlIn the data diagnostics and analytic strategy sections the guideline suggest that information on the following be reported

- in which case to exclude the data of participants from the study at the analysis stage

- how to deal with missing data

- which precise inferential statistics procedure to use

Solution

T in which case to exclude the data of participants from the study at the analysis stage

T how to deal with missing data

F which precise inferential statistics procedure to use: the guideline mentions a strategy, i.e. not a single procedure; it also suggests that this is to be specified for each type of hypothesis

4. Quality and credibility of a preprint: the Precheck checklist

What is Markdown and why do we learn about it?

Markdown is a lightweight markup language for creating formatted text using a plain-text editor. The goal is an easy to write and and easy to read format, even as raw code. It is traditionally used for so-called readme files in software development and extensively as a tool to produce html code for websites. There are several flavors of the language that are used in different places but the basics are the same almost anywhere.

Since a file containing Markdown text only contains plain text and no binary information, it is a lightweight format. Moreover, changes in Markdown files are particularly easy to track.

For a reference sheet of the syntax, please see here: https://www.markdownguide.org/cheat-sheet/

We introduce Markdown here because it will be used in the following episodes of this course and we start to practice it while learning about and using the PRECHECK checklist.

Markdown

Use the online Markdown editor Dillinger to create your first Markdown document including a title, two numbered sections one containg an itemized list and the other a numbered list. Do also include bold and italics font. You can use whatever text you like if nothing else comes to mind you may simple use lorem ipsum

Solution

No solution provided here.

Introduction to PRECHECK

As we have already seen preprints are manuscripts describing scientific studies that have not been peer-reviewed, that is, checked for quality by an unbiased group of scientists in the same field.

Preprints are typically posted online on preprint servers (e.g. BioRxiv, MedRxiv, PsyRxiv) instead of scientific journals. Anyone can access and read preprints freely, but because they are not verified by the scientific community, they can be of lower quality, risking the spread of misinformation. When the COVID-19 pandemic started, a lack of understanding of preprints has led to low-quality research gaining popularity and even infiltrating public policy.

Inspired by such events, PRECHECK was created: a checklist to help assess the quality of preprints in psychology and medicine, and judge their credibility. This checklist was created with scientifically literate non-specialists in mind, such as students of medicine and psychology, and science journalists. The contents of PRECHECK are reproduced here with permission.

The checklist contains 4 items, see below or on the linked website. When using PRECHECK on a preprint read each item and the Why is this important? Section underneath each of them. Check if the preprint you are reading fulfills the item’s criteria - if yes, write down a yes for this item. In doing so use your knowledge of the IMRAD structure and smart searching on the website or the pdf.

Generally, the more “yes” on the checklist your preprint gets, the higher its quality, but this is only a superficial level of assessment. For a thorough, discriminative analysis of a preprint, you also need to consult the related Let’s dig deeper Sections underneath most items. When using the checklist, it is recommended that you have both the preprint itself as a pdf, and the webpage on the preprint server where the preprint was posted at hand. You can also check online whether the preprint has already been peer reviewed and published in a journal.

The checklist works best for studies with human subjects, using primary data (that the researchers collected themselves) or systematic reviews, meta-analyses and re-analyses of primary data. It is not ideally suited to simulation studies (where the data are computer-generated). In general, if the study sounds controversial, improbable, or too good to be true, we advise you to proceed with caution when reading the study and being especially critical.

The PRECHECK checklist

Below you find the checklist together with Why is this important? and Let’s dig deeper Sections. It can also be directly accessed in the Markdown PRECHECK checklist (without the Why is this important? Sections).

1. Research question

Is the research question/aim stated?

Why is this important?

A study cannot be done without a research question/aim. A clear and precise research question/aim is necessary for all later decisions on the design of the study. The research question/aim should ideally be part of the abstract and explained in more detail at the end of the introduction.

2. Study type

Is the study type mentioned in the title, abstract, introduction, or methods?

Why is this important?

For a study to be done well and to provide credible results, it has to be planned properly from the start, which includes deciding on the type of study that is best suited to address the research question/aim. There are various types of study (e.g., observational studies, randomised experiments, case studies, etc.), and knowing what type a study was can help to evaluate whether the study was good or not.

What is the study type?

Some common examples include:

observational studies - studies where the experimental conditions are not manipulated by the researcher and the data are collected as they become available. For example, surveying a large group of people about their symptoms is observational. So is collecting nasal swabs from all patients in a ward, without having allocated them to different pre-designed treatment groups. Analysing data from registries or records is also observational. For more information on what to look for in a preprint on a study of this type, please consult the relevant reporting guidelines: STROBE.

randomised experiments - studies where participants are randomly allocated to different pre-designed experimental conditions (these include Randomised controlled trials [RCTs]). For example, to test the effectiveness of a drug, patients in a ward can be randomly allocated to a group that receives the drug in question, and a group that receives standard treatment, and then followed up for signs of improvement. For more information on what to look for in a preprint on a study of this type, please consult the relevant reporting guidelines: CONSORT.

case studies - studies that report data from a single patient or a single group of patients. For more information on what to look for in a preprint on a study of this type, please consult the relevant reporting guidelines: CARE.

systematic reviews and meta-analyses - summaries of the findings of already existing, independent studies. For more information on what to look for in a preprint on a study of this type, please consult the relevant reporting guidelines: PRISMA.

Let’s dig deeper

If the study type is not explicitly stated, check whether you can identify the study type after reading the paper. Use the question below for guidance:

- Does the study pool the results from multiple previous studies? If yes, it falls in the category systematic review/meta-analysis.

- Does the study compare two or more experimenter-generated conditions or interventions in a randomised manner? If yes, it is a randomised experiment.

- Does the study explore the relationship between characteristics that were not experimenter-generated? If yes, then it is an observational study

- Does the study document one or multiple clinical cases? If yes, it is a case study.

3. Transparency

a. Is a protocol, study plan, or registration of the study at hand mentioned?

b. Is data sharing mentioned? Mentioning any reasons against sharing also counts as a ‘yes’. Mentioning only that data will be shared “upon request” counts as a ‘no’.

c. Is materials sharing mentioned? Mentioning any reasons against sharing also counts as a ‘yes’. Mentioning only that materials will be shared “upon request” counts as a ‘no’.

d. Does the article contain an ethics approval statement (e.g., approval granted by institution, or no approval required)?

e. Have conflicts of interest been declared? Declaring that there were none also counts.

Why is this important?

Study protocols, plans, and registrations serve to define a study’s research question, sample, and data collection method. They are usually written before the study is conducted, thus preventing researchers from changing their hypotheses based on their results, which adds credibility. Some study types, like RCT’s, must be registered.

Sharing data and materials is good scientific practice which allows people to review what was done in the study, and to try to reproduce the results. Materials refer to the tools used to conduct the study, such as code, chemicals, tests, surveys, statistical software, etc. Sometimes, authors may state that data will be “available upon request”, or during review, but that does not guarantee that they will actually share the data when asked, or after the preprint is published.

Before studies are conducted, they must get approval from an ethical review board, which ensures that no harm will come to the study participants and that their rights will not be infringed. Studies that use previously collected data do not normally need ethical approval. Ethical approval statements are normally found in the methods section.

Researchers have to declare any conflicts of interest that may have biased the way they conducted their study. For example, the research was perhaps funded by a company that produces the treatment of interest, or the researcher has received payments from that company for consultancy work. If a conflict of interest has not been declared, or if a lack of conflict of interest was declared, but a researcher’s affiliation matches with an intervention used in the study (e.g., the company that produces the drug that is found to be the most effective), that could indicate a potential conflict of interest, and a possible bias in the results. A careful check of the affiliation of the researchers can help identify potential conflicts of interest or other inconsistencies. Conflicts of interests should be declared in a dedicated section along with the contributions of each author to the paper.

Let’s dig deeper

a. Can you access the protocol/study plan (e.g., via number or hyperlink)

b. Can you access at least part of the data (e.g., via hyperlink, or on the preprint server). Not applicable in case of a valid reason for not sharing.

c. Can you access at least part of the materials (e.g., via hyperlink, or on the preprint server). Not applicable in case of a valid reason for not sharing.

d. Can the ethical approval be verified (e.g., by number). Not applicable if it is clear that no approval was needed.

By ‘access’, we mean whether you can look up and see the actual protocol, data, materials, and ethical approval. If you can, you can also look into whether it matches what is reported in the preprint.

4. Limitations

Are the limitations of the study addressed in the discussion/conclusion section?

Why is this important?

No research study is perfect, and it is important that researchers are transparent about the limitations of their own work. For example, many study designs cannot provide causal evidence, and some inadvertent biases in the design can skew results. Other studies are based on more or less plausible assumptions. Such issues should be discussed either in the Discussion, or even in a dedicated Limitations section.

Let’s dig deeper

Check for potential biases yourself. Here are some examples of potential sources of bias.

Check the study’s sample (methods section). Do the participants represent the target population? Testing a drug only on white male British smokers over 50 is probably not going to yield useful results for everyone living in the UK, for example. How many participants were there? There is no one-size-fits-all number of participants that makes a study good, but in general, the more participants, the stronger the evidence.

Was there a control group or control condition (e.g., placebo group or non-intervention condition)? If not, was there a reason? Having a control group helps to determine whether the treatment under investigation truly has an effect on an experimental group and reduces the possibility of making an erroneous conclusion. Not every study can have such controls though. Observational studies, for example, typically do not have a control group or condition, nor do case studies or reviews. If your preprint is on an observational study, case study, or review, this item may not apply.

Was there randomisation? That is, was the allocation of participants or groups of participants to experimental conditions done in a random way? If not, was there a reason? Randomisation is an excellent way to ensure that differences between treatment groups are due to treatment and not confounded by other factors. For example, if different treatments are given to patients based on their disease severity, and not at random, then the results could be due to either treatment effects or disease severity effects, or an interaction - we cannot know. However, some studies, like observational studies, case studies, or reviews, do not require randomisation. If your preprint is on an observational study, case study, or review, this item may not apply.

Was there blinding? Blinding means that some or all people involved in the study did not know how participants were assigned to experimental conditions. For example, if participants in a study do not know whether they are being administered a drug or a sham medication, the researchers can control for the placebo effect (people feeling better even after fake medication because of their expectation to get better). However, blinding is not always possible and cannot be applied in observational studies or reanalyses of existing non-blinded data, for example. If your preprint is on an observational study, case study, or review, this item may not apply).

Episode challenge

Use PRECHECK for two preprints

Question 1

Select two preprints in psychology and/or medicine that include human subjects. At least one of them should correspond to a preregistration. Review them using the checklist directly in the Markdown file. Create one Markdown file for the assessment of both preprints by copy pasting. Add clear sections for each preprint using Markdown syntax.

Answer at least all yes/no question for each preprint, add an explanation for your choice of answer.

Note: Use your knowledge of the IMRAD structure for smart searching in the articles, the idea is not that you read both articles in detail. Use a search strategy within the pdfs with appropriate terms. Do also look on the preprint servers, they do sometimes contain information that is not directly in the article (e.g. regarding data sharing).

Question 2

Find the preregistration(s) of the preprint and compare.

Question 3

Find the pubilication(s) of the preprint and compare.

Question 4

Look at the preprint server that has been used: what do you find on reporting guidelines? Which reporting guideline would be pertinent for this article? Do you find something on reporting guidelines in the published article? Do you find the policy of the journal regarding reporting guidelines?

Question 5

Find the journal policy on data sharing and comment.

Solution

No solution provided here.

Key Points

The structure of an article represents the steps of the scientific method

The structure of an article helps in finding information and to get started with reproduction/replication

There are some simple questions that can be asked when judging the quality of an article